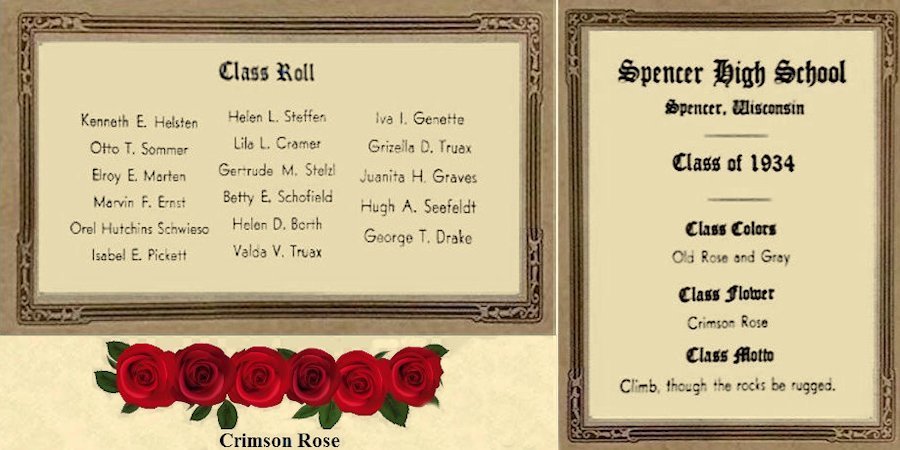

School: Spencer, WI 1934 Class Photo

Contact: History Buffs

Surnames: Hutchins

----Sources: Charmaine Becker's Family Album; Oak Hill School Teacher’s Resource and Curriculum Guide

[Enlargement for Identifications] [Spencer, WI, High School Postcard]

[Contact us if you can identify more students]

*Pictured above is the 1934 graduation class of Spencer High School and the class roll is recorded below.

Orel Hutchins, my mother, is the last girl on the right of the middle row. Charmaine Becker

**********************************************

Spencer High School graduation class of 1927 ?

[Enlargement for Identifications]

My uncle Delbert Hutchins is in the top row 2nd guy from left. I thought maybe

someone could identify the rest of that class?

Charmaine Becker

**********************************************

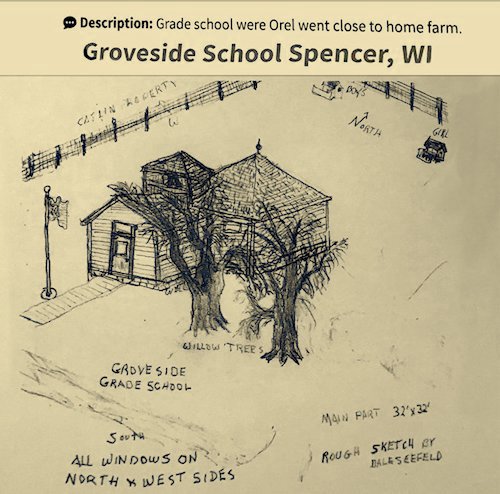

Groveside Grade School #1, Spencer, WI

My mother Orel Hutchins' class, but not sure which one she is. Charmaine Becker

Groveside Grade School #2, Spencer, WI

My Aunt Iva Hutchins is 1st row standing 3rd girl from left. Charmaine Becker

[Close-up for identifications]

|

Orel Hutchins' classmate drew the sketch below of their school with the flag flying near the wooden sidewalk. All windows were positioned to avoid (crosslighting) which was believed to harm the eyes. Notice the "Boys & Girls" outdoor toilets! |

LATE NINETEENTH-CENTURY ONE-ROOM SCHOOLS--All through the nineteenth century the one-room school was frequently the focus for people’s lives outside the home. Besides being used for the daily routine of educating children, it was a place where church services, Christmas parties, hoe-downs* , community suppers, lectures, and spelling bees were held. The school provided social contacts outside the family unit and became an extended family itself. Most of the time school attendance was voluntary and varied from day to day depending on the weather, need for labor at home, and affection for the teacher. Often children were sent to school before the age of six not only to get them out of the house, but because it was thought that school was the proper place for children. Teachers were both male (the schoolmaster) and female (the schoolmarm). If a female teacher married, she had to quit teaching because her most important job then became taking care of the household for her husband. Every family in the community would take care of the teacher’s needs, often providing a place to live until he or she could establish one. In some rural communities, families paid the teacher’s salary while others provided food and staples. Before 1900, rural schools had two terms of schooling during the year–summer term from May until August and the winter term from November through April. It wasn’t until after 1900 that nine month school terms from September to May came into effect. Older boys who were needed in the fields during the growing and harvesting seasons would attend school only during the winter term. Winter term also caused many hardships for the students of one room schools. The cold winter air would blow through the cracks in the building leaving the warm air in the center of the room around the pot-bellied stove. Those farthest away from the stove would freeze and those close to the stove would roast. Heavy wool clothing was a must to keep warm, especially heavy wool socks. However, as children’s cold feet would warm up, it would cause intense itching and constant shuffling of feet under the desks. School usually took place between the hours of 8 a.m. and 4 p.m. Most children who didn’t have a horse or pony had to walk anywhere from a short distance up to three miles to attend class. Chores, such as milking the cow, feeding the chickens and pigs, gathering eggs, carrying in wood, and bringing in water had to be completed before beginning the trek to school. Many late nineteenth-century schools were ungraded, and students were seated according to their general level of ability. Usually, this meant that the younger students were in front and older ones in the back. Students were promoted to the next level when the teacher believed they were ready. Children were exposed to lessons many times; therefore, the younger children would know the lesson well when it came their turn to study it. Older students would sometimes help the younger ones, freeing the teacher to perform other duties. Reading, good penmanship, and arithmetic, were stressed more than the other subjects. These subjects have been referred to as the Three Rs of education– Reading, ‘Riting, and ‘Rithmetic. By adding recitation, an important element of the reading lesson, teachers would sometimes call it the Four Rs. With the scarcity of books and paper, much memorization and oral drilling took place. Students would learn by “rote,” which meant to memorize and recite. To “cipher” meant to do arithmetic problems, either orally or on slate boards. To “parse sentences” meant to explain the meaning and function of each word in a sentence, a precursor to diagramming sentences in the twentieth century. While learning was taking place, good behavior and strict discipline were enforced. Teachers punished those who misbehaved or did not abide by the rules. At the end of the school year, children took an oral exam covering spelling and arithmetic problems, and answered questions on many subjects. This helped the teacher determine the next year’s level of study for each student.

Description of a Typical One-Room School Building--Early one-room schools in America were small and made of thick hand hewn logs or blocks of sod. By the mid- to late-nineteenth century, progress allowed for much larger buildings covered in clapboard siding, board-and-batten siding, stone, or brick. Wooden buildings were unpainted before the 1870s and painted white afterwards. It was during the 1870s that planned designs became the source of information used to build one-room schools. The majority of one room schools were rectangular, though some were square. The buildings ranged from 20 to 30 feet wide by 30 to 40 feet long. Many were built on stone foundations located on the least fertile ground, particularly in a farming community, and were within walking distance of the pupils. Located a short distance behind the school was the outhouse (toilet). Occasionally, two outhouses existed, one for the boys and one for the girls. Roofs were usually simple gabled structures made of shake shingles, tin or as used later in the nineteenth century, mass-produced shingles made of materials available in a particular geographic area. A belfry was usually placed above the entrance to the schoolhouse. This became a status symbol for many nineteenth-century school districts. The tower was both decorative and practical. The bell was used to call children to school, to warn the community of dangers such as fires and accidents, and to ring in the holiday and special occasions. Most rural one-room schools had one entrance door, although a few had two doors, one for the girls and one for the boys. Floors inside the schools were usually made of plank wood or tongue-and-groove wooden flooring. The wood was painted with a light coat of raw linseed oil. Many students spent afterschool hours “oiling the floor.” Two to four small-paned windows were widely spaced on one or both of the long sides of the school. Windows on one side were favored by those who thought that light coming from two directions (cross lighting) could harm the eyes. Therefore, some schools in the 1890s were directed to put in windows on the side were light could fall over the left shoulder. It was a great idea for right-handed pupils, however no thought was given to the left-handed pupil as the left arm blocked out the light. When possible the windows were placed on the north side of the building to provide even, year-round light. Windows were the primary source of light during the day. Kerosene lamps were used for special evening events. Half curtains, usually made by the teacher, were used to cover the windows in order to let light in, but to discourage daydreaming out the window. The cloakroom, located at the back just inside the entrance, was the place where coats, caps, and lunch pails were kept. It consisted of hooks or plain nails placed approximately four feet from the floor, with a wooden shelf along the wall above the nails. Blackboards ran across the front of the room and sometimes down the sides. Several wooden boards from the wall were simply painted black for most one room schools. If the school district could afford them, slate boards were installed. Chalk trays made from two 1-inch by 2-inch by 10-feet strips of wood usually ran the length of the blackboard.

A Typical School Day in the 1890’s-- The one-room school day typically began at 8 a.m., after a 2- to 3- mile hike for children who didn’t own horses or ponies. Long before the students were to arrive, the teacher, with the help of older students who were assigned chores, brought in firewood for the potbellied stove and water for drinking and hand washing. As the school bell rang, students formed two lines —boys in one and girls in another —from the youngest to the oldest. The teacher stood by the door to greet students. The girls entered first, hung their coats on the hooks, placed their lunch pails on the shelf, then stood by their desks while the boys entered accordingly. As the children entered, they “made their manners” by curtsying or bowing to the teacher. The teacher made his or her way to the front and called attention for the Pledge of Allegiance (see next page). After this, the Lord’s Prayer was said or a lesson was conducted in moral instruction using the Bible as a reference. Sometimes a song would be sung. Children were then seated and the roll was called. As the morning exercises began, the teacher would explain the assignments for each grade level. As one grade would “turn, rise, and pass” to the recitation bench, other grades would work on assignments at their desks. Reading was always the first subject taught. Students would be called individually to “toe the mark” and recite a passage from memory or read aloud from a textbook. After a short “turn-out” for privy privileges (girls first, then the boys) and recess, the arithmetic lesson began. Younger children completed their work on a slate board. The teacher checked each younger child’s work and sent him or her to the back of the room while the older students were called to the front to practice their oral math drills. Next came the penmanship lesson, for writing in a good hand was a valuable skill. In the copybooks students wrote their names, the date, and a maxim or two. Again, a moral lesson was taught by discussing the meaning of the maxim(s). The “Three Rs” (Reading, ‘Riting, and ‘Rithmetic) were the most important subjects stressed in the morning before the hour-long lunch session.

When it was time for the noon lunch hour, each row of students went to the shelf in the back of the room to get their lunch pails and a tin cup full of water. In warm weather, lunch could be eaten outdoors. In cold weather, students ate at their desks. After eating, students would have time to play games and help carry in more firewood and water. The bell rang to signal the end of the lunch hour and students lined up to enter the schoolhouse if they were outside. The afternoon sessions began with a grammar/spelling lesson followed by a history lesson. After another short recess and privy break, students read and discussed a moralistic story. This provided an opportunity to polish their skills in elocution as they spoke about the story. The geography lesson ended the coursework for the day, except on the day of the weekly spelldown. Slate boards were cleaned, books were put away, and special announcements were made. The chore assignments for the next day were handed out, and row by row, students retrieved their coats and lunch pails and returned to their desks until dismissed. As students left the room in an orderly fashion, the teacher stood by the door to bid them farewell.

School Discipline and Manners Strict discipline--The teacher was in charge and the families expected the teacher to enforce rules and keep order. Families knew that they were paying to maintain the local school and wanted to get their money’s worth in the education of their children. When the school day began, children were required to file into the one-room school in silence, girls first, in a line youngest to oldest, followed by the boys. No time was wasted for lessons to begin because the business of school was regarded as serious. Students could range in age from 6 to 16 with varying skill levels, so the teacher had no time for foolishness. Students were expected to show respect for their Maker, parents, schoolmarm/master, and friends. They were to “Speak the truth, be honest, be punctual, be clean and be kind.”1 The discipline used for not following rules was strict and swiftly administered. Common forms of discipline were whipping with a ferula, a rod or ruler 15 to 18 inches long used to strike the palms or buttocks; hickory stick spankings; standing in a corner; and sitting on a stool with a dunce cap on the head. Some other forms of punishment included standing with one’s nose inside a drawn circle on the board, memorizing long passages with moral messages, writing sentences over and over, and copying moral messages. The loss of recess, cleaning of the floors, and what was thought to be the worst punishment for boys, sitting on the girls’ side of the room with a bonnet on their head, were all methods used to discipline students in one-room schools. The connection between school and home was a close one with students being punished again upon returning from school. “The schoolmarm/master challenged pupils to ‘keep’ each and every day and likewise reminded the boys and girls to ‘make their manners’ to their parents when they reached home. To make their manners, a girl curtsied, boys bowed or nodded. An apple for the teacher or a bouquet of wild flowers was a kind way to make one’s manners to the teacher. Oak Hill School Teacher’s Resource and Curriculum Guide

|

© Every submission is protected by the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998.

Show your appreciation of this freely provided information by not copying it to any other site without our permission.

Become a Clark County History Buff

|

|

A site created and

maintained by the Clark County History Buffs

Webmasters: Leon Konieczny, Tanya Paschke, Janet & Stan Schwarze, James W. Sternitzky,

|