At 4 a.m., September 14, 1942, Clarence Meinhardt was seated in the rear of a United States Air Force B-25 bomber with a dozen incendiary bombs in his lap. He was over 6,500 miles from his hometown of Greenwood, Wisconsin, flying through the dusty desert skies of Egypt toward a German airbase at Sidi Hanish when an 80-millimeter enemy aircraft slammed into their carrier, plunging it at 250 miles per hour. Meinhardt's bombs were built to detonate a split-second before they struck ground releasing shrapnel intended to maim soldiers. Split second timing would divide the living from the dead. Three times, Meinhardt attempted and failed to make radio contact with his missing crew. Hoping for a better view, he lunged forward only to have his legs fall through a 2-foot raw opening in the plane's floor. His wrists and back were trapped as a turbulent flow of air ripped through him. Suddenly airborne and stunned, he missed the rip chord on his chute. After a second try and just 1,000 above ground, his chute opened. Struggling to unbuckle his chute, Clarence saw his plane and four buddies crash into the desert. He'd had 15 months of flight and combat training and now after just three missions he found himself wounded and burned on the very airbase his squad had intended to bomb. He covered himself with his chute and used his jackknife to cut it into bandages so he wouldn't bleed to death from the shrapnel injuries in his leg. He waited as searchlights crossed the base. At daybreak, the Germans took him by jeep to a first aid tent where he spent the first of his 958 days as a prisoner of war.

Clarence then spent 11 weeks in hospitals in Greece and Italy before facing solitary confinement and interrogation where he was grilled for 8 straight days. He said, "Every single day they'd bring in a different category of personnel, just trying to do anything to get you to talk. I wouldn't give them anything, but name rank and serial number. Finally they figured out that I was as stubborn as they were."

Clarence Meinhardt never forgot the days he spent in a German Prisoner of war camp, waiting, hoping, surviving. Nor will he, nor can he, delete from his memory the numbing notion that more than two years and eight months of captivity almost ended in execution as World War II waned. But chose to forget the bitterness which might have held him hostage for the rest of his life.

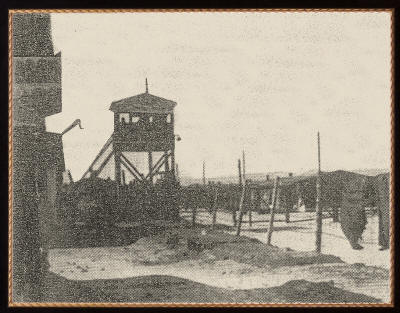

Americans, British, French, Walloons (Belgium), Flemish, Poles, various Slavs, and Russians were all imprisoned in POW camps. Their treatment varied with the best treatment given to the Americans and the British who were protected under the Geneva Convention of 1929. They could not be forced to work but since the Russians had not signed the Geneva Convention, the Germans felt they could do whatever they wanted to them. Therefore, the camp was sectioned off by nationality, with an American captives numbering in the thousands. Americans who disregarded the camp rules were sent to solitary confinement for a month, whereas a Russian, guilty of the same offense, might be shot and thrown on a pit outside the camp. The treatment at the German POW camp, Stalag 17B in Austria (where Clarence spent 2 yrs.), was nearly the worst of any enemy camp with the exception of Stalag 2B.16.

Guards sat in the tower to observe the German Stalag 17B at Krems Austria

As far as mistreatment goes, Clarence said the Americans were not treated as badly as the Japanese prisoners the Allies had captured, "No beatings that I ever heard about, but the trauma was there anyway. Of course, the food was poor--we were fed soup several times with maggots floating around in it. Some of the guys would eat it, maggots and all, and some refused. They did occasionally receive Red Cross packages that helped relieve their hunger. They were given one small hod (bucket) of coal to heat the entire barracks, but supplemented that by tearing the shutters off the camp's windows to burn for additional heat."

Clarence once reported one of the guards to higher authorities saying, "When an American says or does something, it's the truth, or they mean it". Later, the accused guard gave him a dirty look, pulled his gun from the holster and fixed his eyes on him. Clarence thought "oh, oh, this is it". But after making his point, the guard stuffed the gun back in the holster, and walked away.

The POWs were lined up twice daily for roll call and in-between they were left to wander the prison yard. That wasn't work, but it wasn't easy either. Since the men in these camps were more than PVT. 1st Class, (he was a Tech. Sgt.) they didn't have to work like the "lower class", so they frequently spent 8 hrs. a day playing contract bridge, with cards they received from the Red Cross. Clarence had always considered bridge a "woman's" game, but he said it kept monotony from setting in.

Sgt. Meinhardt said escape plans were useless considering the ever-present armed guards and attack dogs. The few escape attempts where prisoners tried to climb the barbed wire fence and were shot on the spot and left to hang as a deterrent to others tempted to try the same.

Trickery and deception were another story as POWs were not above bribing guards with cigarettes for parts to make a radio. The POWs used wire coils and radioactive rocks to build crude crystal radio sets and they'd use them to keep up with the war front news. The imagination and ingenuity of these people was pushed to the limits. Red Cross's dried milk cans were fashioned into stoves to cook food. A shoe lace would be a drive belt, the can a furnace. Wooden slivers ripped from he barracks walls were fuel. They knew the United States was not being bombed and they envisioned returning home at the end of the war, but every POW had days of depression. The group rallied as a whole to bring back those who were down. "I think what got us through was the cohesiveness between fellows," Meinhardt said. "We paid close attention to our buddies. I'm sure we saved many of our fellows from losing their minds. They would have just gone off the deep end." Clarence's own religion helped him cope. "I'm a Christian, I believe in God. I believe in prayer," he said.

In

early 1945, Germany was losing the war and in April, the guards told the POWs

they were leaving camp. The planned destination for the 4,200 men was not

revealed, and Meinhardt didn't learn the true plan until long after the war

ended. "They told us they wanted us liberated by our own forces rather than the

Russians because they hated the Russians," Meinhardt said. The men marched 17

straight days from dawn to dusk. Tired and hungry, they didn't know how close

they came to gas chambers for execution. Meinhardt said, "The only thing that

saved us, was the commander in charge who knew the end of the war was weeks

away. He didn't want to get his neck in a noose and be executed for some

atrocities. Instead of marching us to the gas chambers, we were taken to a

"beautiful evergreen forest" where we lived for eight days, sleeping in

makeshift pine bough shelters."

On May 2, at 6:45 p.m., according to Meinhardt's diary, American troops

liberated the POWs. "The minute the guards saw those American jeeps, they threw

down their rifles. When we saw those jeeps and those uniforms, that was it. We

cheered so loud we almost shook the needles off the trees!" Meinhardt

remembered.

By June, 1945, Clarence was counting his blessing and thankful to be in

Greenwood which had changed little. He said, "It made a better man out of me, by

far. It made me more tolerant, more generous. It made me a better Christian. I

have no hate of anyone, including the Germans. If a person continues to hate

because of circumstances that probably were beyond someone else's control, your

hate is going to haunt you and it's going to destroy you. It'll make you

miserable in the process."

*************

"Clarence left home along with quite a few other inductees from Loyal and Greenwood, but I wasn't there to see him off. He was engaged to another girl, (which I knew, and she was a very nice, religious girl). She apparently tired of waiting for him or feared he'd never come back, and started dating another fellow. When Clarence returned, he was the one to break the engagement, altho' she didn't want to. I suppose he thought she didn't do right by him--should have waited longer for him, but he never talked to me much about it. He was rather emotional, and I think he missed his Mother more than anyone, as he wrote many letters to her, I guess to keep her morale up too. He was very much "for" any person in the military, especially the Prisoners-of-War. He would help them out whenever he could, thus his joining all the military Organizations, esp. the Ex-POWs. In this Org., he got to be a National Director, and would gladly travel out to No. Dak., S. Dak. Iowa, etc. to give them any information to better their lives.

After we were married,

he had some very emotional times yet. He could not sit down to eat a decent

meal--would get nervous and have to get up and go outside, and walk off his

nervousness. I suppose that was the "post traumatic stress'. This went on for

quite a few years, until he joined the several military groups, and got to

talking with the other fellows, and sort of "settled down". I recall one

distinct incident, where my parents thought they were doing good by taking us to

Pittsville, where the Indians had a Pow-wow every year. Their beating

the drums, and singing their type of songs, just "got to him", and he had to get

up and walk away again to settle his nerves.

He was Postmaster of Greenwood for 16 years, and seemed to be very well-liked in

that position. Then after he retired, one of his biggest hobbies, and probably

his only one, was wood-working. He has made several "chests".( like cedar

chests, but not of cedar), made small jewelry chests, folding tables with

checker-board inlays, etc. I will have to say, he was VERY good at that, and

really made beautiful things. He'd spend a lot of time in the basement in his

"work-room", but never seemed to have any bad thoughts then".

Vera Meinhardt (wife of Clarence)

******************

Clarence Meinhardt in 1995, holding a drawing of a B-25 bomber like the one he was in when shot down over Egypt in 1942.

Obit: Meinhardt, Clarence Edward (1919 - 2004)

~Return to the Table of Contents~