|

|

|

Clark County Press, Neillsville, March 28, 2007, Page Transcribed by Dolores (Mohr) Kenyon. Index of "Oldies" Articles

Compiled and contributed by Dee Zimmerman

Clark County News |

|

|

|

Clark County Press, Neillsville, March 28, 2007, Page Transcribed by Dolores (Mohr) Kenyon. Index of "Oldies" Articles

Compiled and contributed by Dee Zimmerman

Clark County News |

March 1937

History of Logging in Clark County

(Fourth in a Series)

A story was told of W. T. Price, one of Clark County’s earliest and largest loggers.

The incident happened at the time the Methodists were building their church at Black River Falls. Some of the building committee went to Price and asked him for a donation toward building the church. Price said, “I can’t give you anything now as we didn’t have a log drive this spring and my logs are tied up on the East Fork. But if you Methodists will pray for rain and I am able to get my logs out, I will give the church $500. Along in June, the rains descended, the floods came and Price’s logs went down the river. After Price returned from the log drive, the church committee was there waiting for his donation.

Price turned to his desk, writing a check for $500 and handed it to a member of the committee. He then said, “The trouble with Methodists is that you pray too hard. You’ve scattered my logs on the banks and up the sloughs, all the way from the East Fork to La Crosse.”

When the ice began to break up on the streams, it was time to start the log drive. The gates on the flood dams were opened, and the logs that had been landed on the ice were driven out first. Then came the work of breaking the rollways; the blocks, which held back the first log nearest the bank, were knocked out. With the logs piled as they usually were, when the first log started rolling, the entire top of the rollway came tumbling down like an avalanche, hitting the water with a big splash. The work was dangerous and the men who broke rollways had to be quick of eye and quick of foot. Only experienced men were assigned that work and even then some were killed or maimed for life. One man’s ear was taken off when a log rolled past him before he could jump entirely out of the way.

After the rollways were broken, cant hooks were used to roll the remaining logs into the streams. After the dams had been emptied of water, the gates were closed to fill the dam for a new flood. As the water rose, many of the logs that had been stranded along the sandbars and banks above the dam, floated. But there were always some logs above the back-waters of the dam that were in the shallow water. These logs had to be rolled into deeper water where they would float. To do this, the men had o work in the icy water, which sometimes was up to their waists, this was called sacking.

After the dam was filled, the gates again were opened and the logs in the pond were driven out through the gates. Care was taken so that the logs were kept straight as they approached the gates, so they didn’t go crossways and form a jam above the dam. Men were stationed above the flume with peevies to keep the logs going through endways. It was surely a sight to see when the logs floated down the river. Sometimes logs that would scale five or six hundred feet, would strike the bed of the river endways, then go end over end, eventually leveling off and to go rushing down the stream.

The crest of the flood picked up most of the logs, which were left on the sandbars and banks from previous floods. But there were always a pocket of still water and eddies where some logs floated out of the current. When the next flood started, drivers working in pairs rode down the stream on logs, looking for the still logs. As they found the still logs, they would use their peevies to pole them back into the current. Occasionally, in spite of all of their care, a log would get crossways of a rock or some other obstruction. With the stream running full of logs, it was only a matter of seconds before a good-sized logjam was started. This type of problem usually occurred where there were high riverbanks and swift water. Pressure of the water and logs behind the pile, caused the logs to pile up to heights of 20 to 30 feet.

As soon as a jam was formed and there was no prospect of moving it, everything on the drive above it was hung up. The flood dams above it were closed and if the jam was on the main river, driving on the tributaries above was stopped below the last flood dam. Then the efforts of the entire driving crew were centered on breaking the jam.

The logs at the head of the jam had to be pried loose and rolled out until the key log was found and pulled out. Then if the jam failed to start, the only practical method was to pick away at the flank logs. A long line pointed down stream, from the center, overcoming the friction at the sides. If the jam failed to move, the dam gates above were opened up, letting a full flood down upon the tail of the jam, hoping the pressure from the rear would start the logs moving. Some-times this failed and the operations had to be repeated.

The work was dangerous. The crew of men had to work from below with the logs hanging over them. At times, there were jets of water shooting out from between the logs, which deluged the men working below.

When the jam started breaking loose, the men had to run for their lives as the pressure from above was tremendous. The logs would tumble end-over-end as the whole jam moved down the river, disintegrating into its component parts.

Starting in the late 1870s, dynamite came into use and many of the rocks and other obstructions, with its aid, were removed and there was less likelihood of a jam forming. If a jam did form, dynamite was sometimes a great help in starting the logs to move, but the key log had to be found and removed before the jam would start to move.

The whole log drive was hard and dangerous, with death lurking at every turn. The men were soaked with water from below and with water from above. No matter how wet it was the log drive had to go on. The log drive started long before daylight and ended only when it got dark, when the men could longer see the logs. For this work, the men received from three to five dollars a day, which for those days was considered very good wages.

In 1864, the lumbermen along the Black River found the need of improving the river for driving purposes. They organized a company known as the Black River Improvement Company, which was incorporated under a special act of the legislature. Some of the objects stated in its articles of incorporation were: building dams, deepening and straightening the channel, closing up chutes and side cuts from the Black River to the Mississippi, erecting booms, piers and lastly but not the least, to charge and collect toll on the running of logs down the river.

This company had complete control of the main river, from the time it obtained its charter, until all of the logs were cut and driven out. Later, at least two other improvement companies were organized for the purpose of competing with the Black River Improvement Corporation. They were the La Crosse Booming and Transportation Company and the Black River Flooding Dam Association. Litigation ensued and these companies were beaten in the Supreme Court, enabling the Black River Improvement Corporation to have control of the river until the end.

In Clark County, the company built two dams. One dam was at Hemlock, near the mouth of the Popple River in the Town of Warner. The other dam was at the Dells in the Town of Levis, about one-half mile below the mouth of Wedges Creek and two and one-half miles above the mouth of the East Fork.

Other extensive improvements were also made on the river, such as clearing the bed of the river of obstructions, closing up the mouths of the sloughs and straightening the stream. This was especially true of the area south of Neillsville.

Before reaching La Crosse, the logs were driven into an immense sorting pond. There many of the drivers found employment for the entire summer months. They sorted logs, poling each owner’s logs into a separate crib, or boom where they were made into rafts and towed to the mill of the owner.

There is where the end and side marks on the logs, became important. It was a fifty-fifty proposition that the side mark was above the water and was caught by the eye much sooner then the end mark and when the logs were so close together, it was sometimes difficult to find the end mark. The driver would have to set spiked boots to the side of the log and whirl it over in the water, until the side mark came into sight.

The drivers became experts in this work and as the water became warmer, there was much more horse play among them. Each driver tried to see if they could roll the other fellow in the water. An old driver told a story on a friend of his, which is worth telling.

Jack Young and John Gardiner, both old river drivers, were driving on the Popple River, just above the Spaulding dam. In the flowage, above the dam, Jack came across a good sized pine log that was split in half, down the middle, with the half floating in the water, split side up. Jack said, “I’m going to turn that log over with the bark side up, so some green horn can jump on it and get thrown in the drink.” No sooner said then it was done. Jack and John rode down to the dam, doing some work. Afterwards, each got on a log to pole back to the flowage. Jack picked out a log, which he thought would be a good one to ride back on, jumped on the log and over it went, quicker than lightning. Jack went to the bottom, with only his hat floating on top of the water, and his peavey went to the bottom of the pond. Of course, Jack had jumped onto the log, which he had previously set as a trap for the other fellow, so the joke was on Jack.

A greater part of the logs that went down the Black River were made into lumber at La Crosse, but not all. There were mills located at Clinton, Davenport, Rock Island, Burlington and other cities as far as Quincy. Logs were hauled on rafts pulled by tugs, down the Mississippi to those cities.

An article was written by Geo. L. Jacques, for a prospectus of Clark County published in 1890 by Satterlee, Tift and Marsh, on the timber resources of Clark County. A statement in that article was: “The cut of pine on the Black River and its tributaries, for the last ten years, has been nearly 200,000,000 feet annually. Of this amount, probably 140,000,000 feet annually was cut in Clark County, the cut on the Eau Claire River, per annum during this same period, was 20,000,000 and on the Yellow River, 5,000,000 per annum.”

In addition to these figures, during the period of 1880 to 1890, saw mills operated in many other parts of the country, too. Much pine, as well as hardwood, was manufactured in those saw mills, having been shipped to market by railroad.

The genuine lumberjack would work all winter at the hardest kind of manual labor and accumulate perhaps from $125 to $150 before the spring drive was over. Then, “Hot Money” was the cry and “Jack” (lumberjack) made tracks to the nearest town or city to spend his hard earned money.

In droves, they came unto the towns or cities and plunged into the wildest kinds of dissipation. The saloons were full, gambling houses did a rushing business and naturally when a man was looking for a chance to spend his money, there were the crew of sharpers on hand to get some of it. In a few weeks, Jack was broke and ready to go back in the woods to make another stake and repeat the performance.

In the camps, after the lumberjacks work was done, there was always something going on for amusement. Usually there was someone in camp who had a fiddle or an accordion and aside from listening to music, they would often have a “stag dance” to whittle away the time.

Checkers and nine-men Moriss were also poplar among the men, as well as many other games that were played.

Then there were lively games such as “shuffle-the-brogan” and “hot back” that occupied their time.

In some camps, there were usually some good singers who could sing the popular songs of the day as well as the regular camp songs, such as “Breaking the Jam at Gerry’s Rock.” Another song, that was popular in camps, began as follows:

“I am a jolly shanty boy, as you will soon discover. To all the dodges I do fly; a hustling pine-woods rover,” of which there were eight or ten verses. There were also many other songs that they sang.

There were also the story-tellers in every camp, which must have been the way that the Paul Bunyan story originated. Also there were stories about the mythical animals such as the hodag, the snow snake, and the rac-a-re-bob, to catch the unwary tenderfoot.

When the Fox River land in the Town of York was being logged, some of the camp men were telling, one night in camp, about seeing tracks of a rac-a-re-bob when they came back to camp. They hoped one of the new boys would bite on the story and the other men, of course, filled in on what a terrible animal it was, a combination of panther, grizzly and timber wolf. One young man, whom we will call Bill, was thoroughly frightened and it showed.

The next morning, one of the men dressed in a large fur coat and left in the dark ahead of the other men, into the woods. As Bill and his crew friends passed a large bush pile, there was a crashing of brush followed by screams, growls, shrieks and moans. Then in the semi-darkness; a furry object jumped out from behind the brush pile. Bill took off running, well in the lead of the other men. Of course, as soon as Bill got in the lead, the other men stopped running and waited for their comrade in the fur coat to catch up with them. Bill kept running until he met a teamster coming with supplies, from Spokeville. The teamster asked Bill what the trouble was, as he saw Bill ws sweaty and out of breathe. After being told what happened, the teamster tired to persuade Bill to return to camp with him, as the guys had put “a job” on him. But Bill couldn’t be convinced. He said, “If you had seen and heard what I did, you would be scared too.” That ended Bill’s working in the logging camp.

•••••••••r

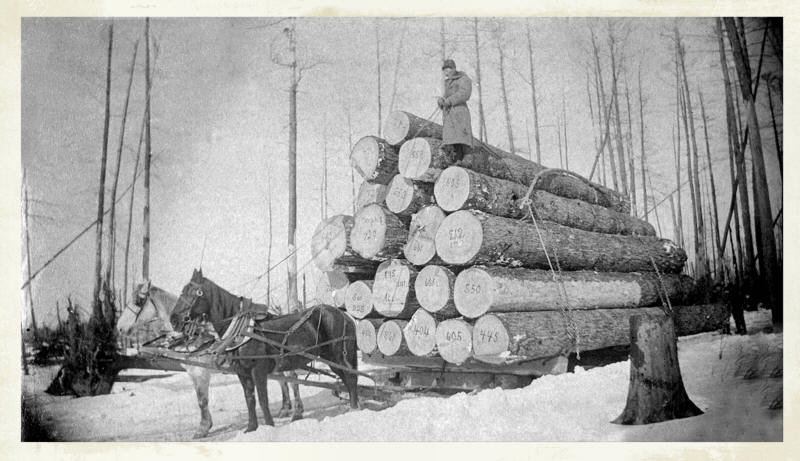

This load, of 23 large logs, represented the immense virgin pine timber that was taken from land along the Black River, in Clark County during the 1870s. One of the early pioneers stated that when driving a buggy, from Neillsville to Greenwood during the day, the sunlight couldn’t be seen due to the tall pine timber along the trail.

¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤

|

© Every submission is protected by the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998.

Show your appreciation of this freely provided information by not copying it to any other site without our permission.

Become a Clark County History Buff

|

|

A site created and

maintained by the Clark County History Buffs

Webmasters: Leon Konieczny, Tanya Paschke, Janet & Stan Schwarze, James W. Sternitzky,

|