“Witcher” shares information on cleaning and repairing gravestones

Contributed by Dolores (Mohr) Kenyon

|

|

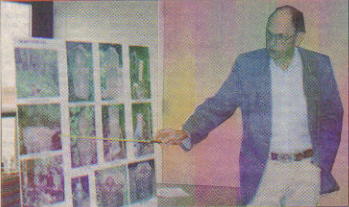

Ralph Hendersin points to a gravestone he cleaned in a Monroe County cemetery. Hendersin gave a workshop on gravestone cleaning and restoration at the Black River Falls Public Library April 1.

Banner Journal (Black River Falls, WI) April 5, 2006

By Pat McKnight

Ralph Hendersin has had to demonstrate more than once his ability to locate graves through “witching” to prove that he can find hidden burial sites.

Hendersin, along with his wife Janet, have made cleaning and restoring worn or damaged gravestones their life’s mission. The couple spoke at a workshop on gravestone cleaning and restoration sponsored by the Black River Falls History Room of the Black River Falls Library on April 1st.

Hendersin’s efforts to clean and repair grave markers, has also extended to locating unmarked graves. He does this with “witching rods”. The rods not only tell him where the burial site is, the rods tell him whether a woman or a man is buried there.

“I don’t know why any of this works,” said Hendersin, “but denying the obvious doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist.”

The witching rods Hendersin uses are two welding rods about the thickness of the wire used in clothes hangers. A 90-degree bend is put into the rods about four inches from one end. Hendersin puts the four inch end of the rods into his loosely closed fist and holds the rods straight out in front of him.

As he walked toward a man sitting in the audience at the workshop, the two rods moved so they crossed each other when they were positioned over the man’s head. They moved apart, pointing away from each other when they were positioned over a woman’s head.

Hendersin says that the rods have even worked for gravesites containing cremation remains.

To find lost graveyards, the Hendersins use hearsay, historical records and latest technology. They will use a global positioning system to help locate a site that is on private property.

He recommended to the audience that they contact the owners of the property to ask permission and to let them know what they will be doing at the gravesites.

While towns are required to mow the lawns and such maintenance at the cemeteries under their jurisdiction, they are not required to maintain the grave markers.

Hendersin showed before and after photographs of some of the gravestones that have been restored. He had examples of gravestones that were worn, covered with moss or lichens, leaning or broken.

For cleaning the stones, he recommended using a product called Orvus. The cleaning compound can be found where animal-care products are sold. According to Hendersin, it is the only solvent he has found that won’t leave a residue or cause a stain to reappear later.

Brushes used for scrubbing the stones should have nylon or polypropylene bristles. Hendersin says that wire brushes do too much damage to the stones.

“The one thing you want to keep in mind is do no damage,” said Hendersin.

He and his wife Janet are from Sparta and have worked in a number of cemeteries in that county. They have restored some of the gravestones of their own ancestors, but the gravestones of non-relatives are as meaningful to the couple.

“When we go into these pioneer cemeteries, they (the deceased) become people to us,” said Janet. “We live with them for awhile (as they work on their markers).”

To repair broken gravestones, Hendersin has developed a mixture of epoxy and cement for filling cracks and holes. The mixture can even recreate stone that has broken away.

Sometimes he has to take the stone home to work on it. When he does this, he leaves a sign that indicates he has removed the stone for repair. Hendersin claims the more porous the stone, the harder it is to restore.

In describing the work he did on the gravestone of a veteran, he gave the reason for why he takes on the work. “I got a warm, fuzzy feeling when I drove away,” stated Hendersin.